History of transportation on the Silk Road

The Silk Road is the longest and historically most important land trade route in the world. The trade began thousands of years ago because merchants discovered that the transportation of goods was profitable and that silk was one of the main trade items.

The Silk Road originated in the Western Han dynasty (202-8 years ago). Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty sent Zhang Qian out of the western region. He started from the capital Changan (now Xi’an), through Gansu and Xinjiang, to Central Asia, West Asia, Iran, Persian Gulf and to the land of the Mediterranean countries. The Silk Road’s original role was to transport the silk produced in ancient China.

Through trade and travel along the way, cultures throughout Eurasia developed economically, technologically, and culturally, and religions and ideas spread east and west. The Han, Tang, and Yuan empires prospered especially due to international shipping, but during other times, trade stopped for various reasons.

Why did the Silk Road trade begin?

The region of China was isolated from the civilizations of the West by the highest mountains in the world, some of the largest and most severe deserts, and long distances. In between, nomadic people raided travelers and merchants.

However, the Shang (1600–1046 BC), Zhou, and Han dynasties dominated the production of several types of products that were important and unique as international cargo, such as silk, porcelain, and paper, and these were highly prized in the West.

But to get west, there were only two land routes. Sea travel was still too primitive. An overland route passed through the Gansu Corridor, extended west to Xinjiang, and then divided into several routes. This is called the Silk Road. The other called the Tea and Horse Route started from Yunnan and Sichuan and crosses Tibet.

Products such as silk were very valuable to those in Central Asia and as far away as Europe. They paid with precious metals, animal skins, and some of their own manufactured goods, such as woolen goods, rugs, and glass products that were prized in the East.

The prehistoric beginnings of the Silk Road (c. 5000 BC – 3000 BC)

Chinese silk fabrics were light and easy to transport, and a highly valuable export item.

Prehistoric trade and travel across Eurasia are poorly understood, but there is evidence of international shipping and travel to Xinjiang as early as 4,000 years ago. In the Shang Kingdom (1600-1046 BC), jade was highly valued and they imported jade from an area of Xinjiang.

In the first millennium BC, people brought silk to Siberia through the Gansu Corridor on the northern branch of the Silk Road. Silk was found in a tomb in Egypt dating to around 1070 BC., suggesting that even at this early time, silk was traded in Eurasia.

Zhou dynasty (1045–221 BC): early Silk Road trade

It is known that around the year 600 AC., gold, jade, and silk were traded between Europe and Western Asia and the advanced states of the Zhou dynasty (1045–221 BC). The silk was found in a 6th-century tomb in Germany.

Around 300 BC, civilizations active in international road transport on the Silk Road included Ancient Greece, Persia, Yuezhi, and the Qin State that controlled the eastern part of the Hexi Corridor (or Gansu Corridor in Gansu Province). This corridor is a huge long valley that stretches from Luoyang to Xinjiang.

Sogdian Merchants (200 BC – 1000 AD): The Important Middlemen

To reach Western Asia and Europe, the products were transported through the Sogdian territories west of Xinjiang into present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and from the 2nd century B.C. Until the 10th century, the Sogdians dominated the Silk Road trade.

They were the most prominent traders and middlemen on the Silk Road for more than 1,000 years. They established a trade network across 1,500 miles from Sogdia to the Chinese empires. The common lingua franca of the trade route was Sogdian. Many Sogdian documents were discovered in Turpan.

The Han Empire (206 BC – 220 AD): Trade developed

During the Han dynasty era, large caravans of hundreds of people traveled between Chang’an and the West.

The Silk Road trade got off to an excellent start through the work mission of Zhang Qian (200-114 BC). Originally, people in the Han Empire (206 BC-220 AD) traded silk within the empire from the interior to the western borders, but internal trade was hampered by attacks by small nomadic tribes in the commercial caravans.

To protect their internal trade routes, the Han court sent General Zhang Qian (200–114 BC) as an envoy to build relations with the Central Asian states and find their former allies, the Yuezhi people, who had left Xinjiang and the Gansu Corridor after they were defeated by the Xiongnu in 176 BC.

Starting from Chang’an (today’s Xi’an), the capital of the Western Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 9), and crossing the vast western regions, Zhang reached the important petty kingdoms of Loulan, Qiuzi, and Yutian and established trade and relationship with them.

Zhang’s officers went even further into Central Asia. He arrived in Sogdia and was surprised that the Yuezhi had settled in the Fergana Valley region and had a high level of civilization, craftsmanship, and wealth. The townspeople operated a rich trade network with India, the Near East, the Middle East, and the countries of the ancient world.

When Zhang Qian returned to China, he told the emperor about the rich countries to the west, describing the large and fast “winged horses” that were better than the empire’s races. The emperor wanted these horses to use in his wars against the Xiongnu and other tribes, so trade embassies were soon sent to Central Asia to obtain the horses. Among the gifts they sent was silk which was highly prized for its beauty and novelty. So, the Silk Road trade started in a big way.

The countries that Zhang and his delegation visited sent his envoys to Chang’an, and merchants began traversing trade routes to bring silk and pottery to other parts of the world. The Han imported Roman glassware and gold, silverware from Persia, and much silver, gold, and precious stones from Central Asian countries, among many other imports.

Three Kingdoms Period (220–581): Trade ceased

After the Han Empire fell in 220, from 220 to 581, the region was divided into three major warring states. At the same time, during the 200s, barbarian attacks on the Roman Empire increased, and this further hampered trade with Europe.

During the 200s as well, the Han’s attacked states to the west of the Roman Empire, and this war diminished trade in Central Asia. Around the year 400 AD, the Roman Empire collapsed. For these and other reasons, there was a decline in trade through the Gansu Corridor westward to the Tang Empire.

Tang dynasty (618–917): Trade flourished

In the early Tang dynasty era (618–917), the Silk Road route in Xinjiang was controlled by Turkic tribes. They allied with small states in Xinjiang against the Tang.

The Tang dynasty later conquered the Turkic tribes, reopened the route, and promoted trade. Trade with the West boomed.

The Sogdians played an important role in the trade of the Tang dynasty and rose to particular prominence in the military and court government of the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD). Sogdian merchants and diplomats traveled as far west as the Byzantine Empire, establishing a trade network that stretched some 1,500 kilometers from Sogdiana into Tang territory.

The famous monk Xuanzang (602–664) traveled the Silk Road during this period. He started his journey from Chang’an (Xi’an today), passed through the Hexi Corridor (the area west of the Yellow River), Hami (Xinjiang Region), and Turpanand and continued west to India.

At the time, it was commonly believed that people in such states were brutal and savage, and Xuanzang was surprised by the warm reception he received along the way. His report helped improve the Tang government’s relations with these tribes and kingdoms.

However, in the year 760 d. C., the Tang government lost control of the western region and trade on the Silk Road ceased.

Song dynasty (960–1279): trade ceased once again

The Tang Empire ended in 907, and a few decades of warfare followed until the Song Empire emerged. The Song Empire was powerful, but they were not in control of the Gansu Corridor.

The Western Xia was a kingdom in the northwest that controlled access to the Gansu strategic corridor. The Song dynasty thought that if they could reclaim the land of Western Xia, perhaps they could re-establish the lucrative Silk Road trade that benefited the Han and Tang dynasties. They tried to conquer the country, but could not.

Then, in 1127, the Song court was forced south of the Yangtze River, and the remaining Southern Song Empire was even further from the Silk Road. Then in 1200, the Mongols attacked them.

However, as the Mongol Empire expanded into Central Asia and Europe before the fall of the Southern Song Empire, they promoted and protected trade on the western routes of the Silk Road.

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368): trade reached its zenith

Trade on the Silk Road was revived and reached its zenith during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), when the Mongols promoted trade in their huge empire that stretched across Eurasia. Genghis Khan conquered all the small states, unified China, and built a great empire under his rule.

Marco Polo (1254–1324) traveled along the Silk Road visiting the Yuan capital Dadu (now Beijing). In his famous book on the Orient, he mentions a special board-shaped passport. It was issued by the Yuan government to merchants to protect their trade and free movement within the country.

Another preferential treatment was also given to merchants, and trade boomed. Silk was traded for medicines, perfumes, slaves, and precious stones.

Why did China’s Silk Road trade end?

Technological changes, political changes in the Ming Empire, and European production of silk, porcelain, and other traditional export products caused the decline of the Silk Road.

In the 1500s, European trading ships regularly sailed the coastal waters of the Ming Empire, and as sea travel became easier and more popular, trade along the Silk Road declined. At the same time, it became more difficult to travel by land. Ship transport was faster and cheaper.

The conquest of the Byzantium Empire and Ottoman control of western Asia kept Europe and the Ming and Qing empires separated from the West, and overland travel became dangerous. While the silk-for-fur trade with the Russians north of the original Silk Road continued, by the end of the 14th century, trade and travel along the route had declined significantly.

In the 1400s, the Ming court policy changed to isolationism. They stopped the Silk Road trade. Also, there was less demand for silk and porcelain in the West because they produced their own. In the 1100s, the Italians began to produce silk and textiles, and by the 1400s, Lyon was a major center for the production of silk textiles for the European market. By the 1700s, Europeans were also producing porcelain and partially satisfying domestic demand.

After this, some of the Central Asian Silk Road routes, especially those in high mountain areas in Tajikistan, Afghanistan, China, Pakistan, and India continued to be used until the early 20th century.

Brief revival during the Japanese attack (1937–1945)

The Japanese attack on China forced the revival of the land route to Europe. By 1939, the Japanese controlled Chinese coastal waters, and the Kuomintang government asked the USSR to build an automobile highway that partially coincided with the northern route of the Silk Road. The highway ran some 3,000 kilometers from the Turkestan-Siberian Railway (Turk-Sib) to Lanzhou.

In 1940, Britain closed the Burma Road to China at the behest of Japan, and the Soviet Silk Road became the only avenue by which China could receive aid from the outside world. From 1937 to 1941, the Soviets supplied armaments and this helped the Kuomintang and Communist armies to survive. After 1945, maritime trade was revived, and airplanes also helped transport goods.

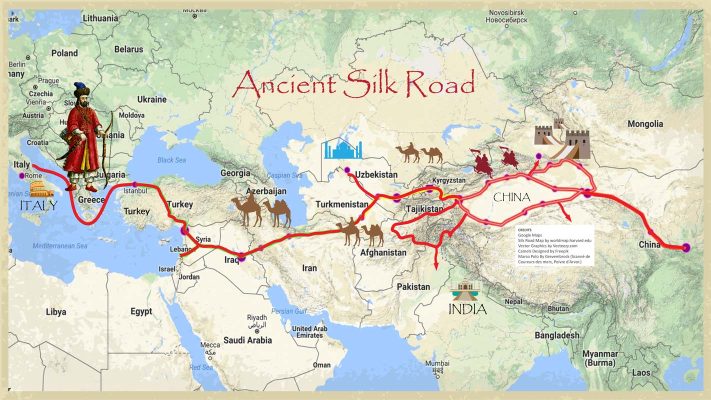

Various routes of the Silk Road (c. 1300 BC – 1400 AD)

It’s not really just one road… The Silk Road is actually the collective name given to a series of ancient land trade routes that linked China, Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe. The Silk Road trade with China passed through Xinjiang.

The long and winding routes in northern China followed the Gansu Corridor, a huge valley that is 1,000 kilometers long through Gansu province. The eastern end of the valley opened up at Lanzhou, and the western end of the valley opened up near Dunhuang.

The routes began in the ancient capital cities of Luoyang and Xi’an, crossed the Yellow River at Lanzhou, and then followed the Gansu corridor into Xinjiang. At Dunhuang, the route was divided in three ways: the northernmost branch crossed north around the Tianshan Mountains, and the other two crossed north and south of the Taklamakan Desert or the Tarim Basin.

The Southern Silk Road or the Tea and Horse Route (700–1930)

In contrast to the north of the Silk Road, the main export product of the Tea and Horse Route was tea.

However, the empires of the Ming and Qing dynasties continued to trade silk, but especially tea, with Tibet and South Asia through the very old Tea and Horse Route (Chama in Chinese) trade routes. This trade route is also called the “Southern Silk Road”.

Yunnan and Sichuan were great exporters of tea for more than a thousand years to the Tibetan Empire. In exchange, the Tibetans exported horses and various products.

However, during modern times, maritime trade and the availability of Indian and Ceylon tea made the Tea and Horse trade route obsolete.

The Maritime Silk Road (1112 BC – 1912)

The Maritime Silk Road grew in importance from the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC). Due to the Arab conquests and wars in the West, maritime trade increased in the Tang era. With the Mongol invasion of Central Asia, maritime trade reached its peak during the Song dynasty (960–1279) with Song trading junks controlling most of the trade.

Sea trade then declined again in the Ming era (1368–1912) due to imperially imposed prohibitions on sea trade. During the Qing dynasty, filling the gap, the Europeans took over the trade routes and their ships carried most of the goods.

The new Silk Road (21st century)

Silk Road trade is reviving in part due to improved land transportation technology. The Chinese government has been talking about building highways and bullet train lines to connect China and Europe as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). These would follow the old routes and use the mountain passes like the Gansu Corridor to Athens.

However, not much has been built yet. There is a bullet train line between Lanzhou and Urumqi, but there is none to the west of Urumqi yet.

What was traded on China’s Silk Road and why?

Silk was generally the favored export of China’s empires that traded with Western countries along the Silk Road from the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) onward. But there were also other important export of goods. In exchange, China received many types of goods ranging from precious metals to horses, weapons, and manufactured goods up to modern times.

Exported products

The types of goods exported from China during the Silk Road’s at least 3,000-year history changed over time, but silk was generally the most precious export.

Silk

Silk, the most luxurious of all fabrics, was light and easy to pack, and was the favored export product along the Silk Road. It was made almost exclusively in China until the Japanese discovered the secret around the year 300.

It was then made in certain Central Asian countries and Byzantium in the 5th or 6th centuries. By the year 1100, silk was being produced in Italy.

Porcelain

Porcelain was another invention that was appreciated in the West. It was during the Han dynasty era that the first brightly colored porcelain types were made and shipped to the west, and especially during the Tang and Yuan eras, fine porcelain pieces were produced in large quantities and exported.

Europeans didn’t learn how to make porcelain until the 1700s.

Other valuable exports

Bronze ornaments and other bronze products, such as ornate bronze mirrors, were exported as was lacquer. Paper was invented during the Han dynasty era and was also appreciated in the West. Traders also carried tea and rice.

Imported products

Gemstones and Jewelry

Jade has always been a favorite semi-precious stone in the region starting with the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BC) which imported jade from Xinjiang, central Asia. This was one of the first imported products.

Horses

The various empires have always needed horses. The local breeds were considered too small, and they wanted better horses to use in battles against nomads and enemy cavalry. This is actually what prompted the Han court to start the regular Silk Road trade in the 2nd century BC. c.

Precious metals

Of course, people in the west commonly paid in gold and silver. The Roman Empire was a major exporter of gold and silver. Silver metal and coins also came from Central Asian countries, and Persia sent famous fine silver items.

Wool items

Sheep were largely unknown in the eastern empires. Wool products, rugs, curtains, blankets, and rugs came to China from Central Asia and the eastern Mediterranean. These products impressed them because they were not familiar with the methods of wool processing, carpet making, and weaving. Parthian tapestries and rugs were highly prized in ancient empires.

Other valuable imports

Central Asian countries exported camels that were prized in the Han and Tang empires. They also sent military equipment, gold and silver, and semi-precious stones.

First, the Romans and then Samarkand made glassware that was especially valued due to its high quality and transparency. The glassware was novel. It was considered a luxury good. Other imports were animal skins, cotton cloth, gold embroidery, and sheep.

Conclusion

Despite what its evocative name suggests, the Silk Road was not a route in which this fabric was mainly exchanged. Not a single route or path that crossed the Asian continent to unite the Far East with the West, but a network of trade, cultural and technological exchange routes that radiated from Central Asia. For 1,500 years it connected China with the Mediterranean, playing a decisive role in the transition to the Modern Age.